Fascinating scientific experiments at Isuntza 1 Cave in the Basque region of Spain have attempted to replicate Paleolithic lighting conditions. The work is inspired by a desire to understand and recreate how Paleolithic cave dwellers might have travelled, lived in, and created art in the depths of their caves.

The results have been published in the open-access journal PLOS ONE by researchers from the University of Cantabria, Spain.

How Paleolithic Cave Art Was Created Without Artificial Light

“Humans cannot see in the dark; therefore, they need light to enter the deep parts of caves, and their visits to those places depend on the physical characteristics of their lighting systems”, the study authors write. This forms the premise of this fantastic research undertaken by the group led by Professor Angeles Medina-Alcaide.

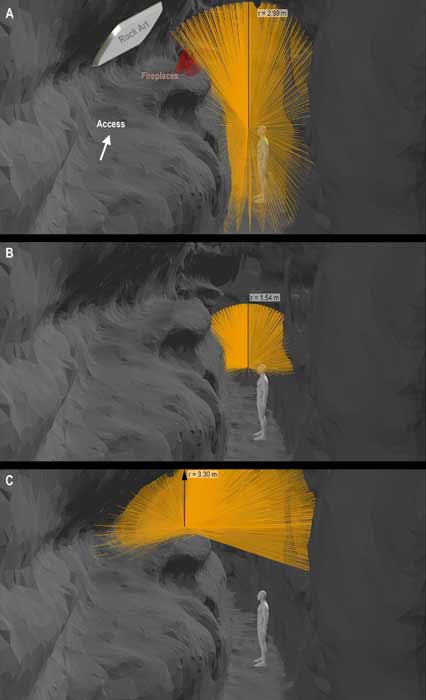

Three common types of Paleolithic lighting systems were recreated – torches, grease lamps, and fireplaces. This was juxtaposed with the type of light available (light intensity and duration), area of illumination, and color temperature, to understand how the cave environment can be used.

Images of the new study’s fireplace experiment. (Medina-Alcaide et al. 2021/PLOS ONE)

The researchers replicated and assessed their Paleolithic lighting systems based on archaeological evidence at several Paleolithic caves with cave art across Southwestern Europe. They used torches made from ivy, juniper, oak, birch and pine resins. Additionally, two stone lamps using the animal fat of cow and deer (taken from their bone marrow), and a small fireplace made with oak and juniper wood were reconstructed. The researchers explain in their paper:

“This study has quantitatively characterized, for the first time, the main luminosity aspects of Paleolithic lighting systems based on archaeological and empirical data. The artificial lighting was a crucial physical resource for expanding complex social and economic behavior in Paleolithic groups, especially for the development of the first palaeo-speleological explorations and for the origin of art in caves.”

Different Kinds of Paleolithic Lighting Systems

The finds were interesting, with the starting point being that each lighting system had a unique and different response, suggesting that a singular form of lighting could be employed across different contexts. To keep them from burning out, wooden torches made of multiple sticks lasted the longest when it came to cave exploration and crossing wider spaces, projecting light up to 6 meters (19.6 feet) in all directions.

Wooden torches also prevented the user from being blinded or burnt, despite a high light-intensity. The average life span of such a torch was 41 minutes, ranging from 61 (the longest) to 21 minutes (the shortest), reports CNN. Relighting the torches was easy as it required a shaking from side to side to re-oxygenate, but the smoke production was a serious concern.

Photograph of Torch 1 in the Paleolithic cave lighting experiment. (Medina-Alcaide et al. 2021/PLOS ONE)

“We walked for 20 minutes inside the cave until the light was getting low. It was pretty striking that the light from the torches is really different from the artificial light we are used to,” said Diego Garate, an author on the study.

Grease lamps were the go-to form of lighting for smaller spaces. The easiest way to understand this light source is to compare it with the light intensity of a small candle. A single-wick grease lamp provided light up to 3 meters (9.8 feet) in all directions, but that space could be increased be adding more wicks.

Photograph of the experiment with stone lamps. (Medina-Alcaide et al. 2021/PLOS ONE)

The lamps were poor transit lighting mechanisms, burning out quickly in that aspect, and as floor lighters, thereby providing little assistance while navigating the maze of caves. The team found that the lamps were a great accompaniment to torches since their smoke production was much less and they burned for over an hour with ease.

The sole fireplace that was constructed burnt out after 30 minutes and was very smoky and uncomfortable to be around. Although the researchers did add that in all probability, Paleolithic cave dwellers had a better sense of air currents and draughts that blow in the caves, and probably constructed their fireplaces accordingly.

Representation of the range of the illuminance (lux) of the three analyzed lighting systems. A. Wood torch. B. Portable grease lamp. C. Fireplaces with wood fuel. (Measurements made in ArcScene™ by ArcGis ® based on the data from the experiments). (Medina-Alcaide et al. 2021/PLOS ONE)

The Advantages that Early Man Had as a “Caver”

There were other facets of evolutionary biology that early man held over the current research team. Firstly, the concept of artificial lighting did not exist, and the transition was never needed for early man. Secondly, there was a sense of comfort and familiarity with the caves, even within the deep recesses and crevices that early man had. They made concerted efforts to go deep within these spaces to paint.

“They know how to move and manage inside the cave, which is really difficult for us even with helmets and rope. At that time, it was obviously harder. They had to move with a torch in their hand, which is dynamic and gives off this red light,” he said. They could have made drawings just at the entrance of the cave without any problem. They wanted to do it in these narrow places and go very deep inside the caves. That was part of it,” concluded Garate.

Top image: Paleolithic cave dwellers used torches, lamps, and fireplaces. Source: Gorodenkoff /Adobe Stock

By Rudra Bhushan

References

Hunt, K. 2021. How our ancestors conquered the dark to produce the world’s oldest art. Available at: https://edition.cnn.com/style/article/cave-art-stone-age-lighting-scn/index.html.

Medina-Alcaide, A., Garate, D., et al. 2021. The conquest of the dark spaces: An experimental approach to lighting systems in Palaeolithic caves. PLOS ONE 16(6). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0250497.